Behind The Sound Of ‘Chevalier’ With Award-Winning Supervising Sound Editor – Greg Hedgepath | Interview

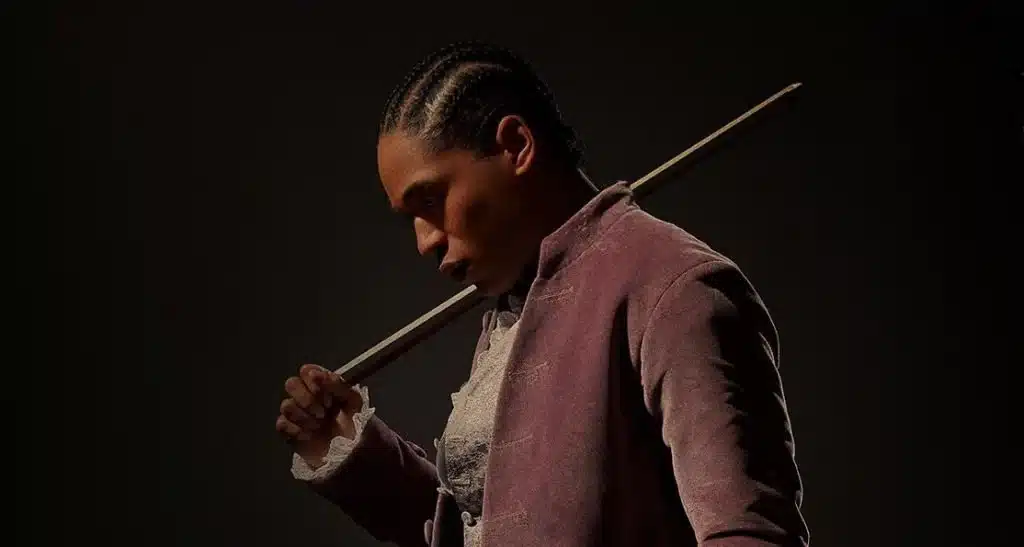

This week, Searchlight Pictures has released a brand new film, “Chevalier”, which is about Joseph Bologne, an illegitimate son of an African slave and a French plantation owner, who rises to improbable heights in French society as a celebrated violinist-composer and fencer, complete with a love affair and falling out with Marie Antoinette.

Recently, I got to speak with Greg Hedgepath, a supervising sound editor with a list of impressive credits spanning over 40 years. Greg’s work includes “Frozen”, “The Princess and the Frog”, and “Chevalier”. In addition to working on “2 Fast 2 Furious”, “The Hunger Games”, “Straight Outta Compton”, “Howard The Duck”, and “Footloose.”

Check out the full interview below:

Could you introduce yourself and share some details about what a supervising sound editor does?

Hi, I’m a supervising sound editor based in Los Angeles, and you’re actually in my home studio. You can’t see much of it, but a lot of us work from home, and so I, as a supervising sound editor, I’m in charge of the overall quality of the sound that comes out of the mixing stage. There’s a big room with the console, we call it the dub stage or mixing stage. So all the pieces that come together before that, the dialogue, the voice replacement, which we call ADR, the shape of the music, sound effects, background, sound design. Sound design is creating something new that never existed before, like an animal roar that you’ve never heard before, like the velociraptor in Jurassic Park or whatever. So that’s the kind of thing I do.

I’m responsible for hiring the crew. So that means I need to know various editors around town and who’s good and who’s not. Most of the people in Hollywood are great. Some people are better at certain things, like some people are good at guns, so I have to know that’s a gun guy. He’s a car guy. This woman is good at such and such. So I hire these people and I also have to watch the budget, so I have to manage the budget. So what happens is, at first we get a script. When I say we, that’s my crew. I work with a woman named Bobbi Banks, who’s my ADR supervisor and partner. And so we get the script, we go through it. First, we’ll usually read it just for the story and then to get a sense of it and the arc of the story, and then we’ll go through a second time and make notes for what we might need or additional things we might want to add in, different sound ideas to propose to the filmmakers.

And so now we know how many weeks are in our budget, so how many weeks we have to do X amount of work. We’ll have maybe four weeks to prep, and then we’ll have a director’s cut screening where we screen to an audience, and then we’ll do some changes and maybe do two more. And then after that we’ll have more time, maybe six, eight weeks, to really prepare the sound properly and get it ready so we can start mixing it. Then when we go on the mix stage, we do what’s called pre-dubbing, pre-mixing, where we take all the elements because we may have thousands of elements between dialogue and effects and different things. Take the elements, and then we’ll funnel them down to different groups, like here, these are the main actors, these are the background actors, these are the main effects here, these are the car engines, brake squeaks, bullet whizzes, bullet impacts, gun mechanisms.

So we have all these different groups of sounds that we have put them into manageable groups. Then we get to the stage and we start mixing those all together with the music, which comes in from the composer. And we start doing what’s called a final mix. And once we get into that mode, everybody gets involved. That’s when the director’s there, producer’s there, studio people come in and see it, and we will play it for everybody and we’ll go through several rounds of changes, play it, do more changes, come back, do more sound changes. And then when we’re done, then we do what’s called a print master where everything gets married down to just one track that has everything on it, and then that gets married to the picture. And that’s a very simplified way of how it works.

What was the biggest challenge working on “Chevalier”?

I guess you could say there were several challenges because it’s a period picture. So I think one of the things when I interviewed with the director, Stephen Williams, I told him, I said, “I’ve been waiting for a picture like this,” because I’ve done horses and wagons and I’ve done different ambiances, but I’d never really done them in a period picture, and I wanted everything to be correct, so that was a challenge. So we’re in France of the late 1700s, and so streets are cobblestones. So you can’t just use regular carriages going down streets, you have to have them on cobblestones. And then also, trying to think of what would the various sounds be heard that we would be hearing in France and putting those together and putting them in the right space. So that was a challenge, shaping France at that time.

And it was the beginning of the French Revolution, so as we go through the film, the voices are starting to build up more, and there’s more mayhem in the streets. So always keeping that going, that theme going, we had to do that. That was a challenge. And then also, of course, a big challenge was the music, and music was key in this film so everything else had to fit around it for the most part, but it came out stunning. I think the music in this film sounds good. So that’s a challenge. And also, because there were crowds everywhere, we had to really shape the crowds and record crowds chanting and stomping their feet and doing all kinds of things. And sometimes when you’re recording that stuff, you’ll have an idea how it integrates in with everything, but you never know how everything’s going to play together, because you may think this is a big moment to have a cheer, but the music may do a big crescendo there, so somebody’s got to win. Both sides can’t win, so what’s more important? So there are those decisions that we’re making through the whole process.

There were even more challenges. I don’t want to give away the plot too much to people who haven’t seen it, but there’s just some really interesting moments. There’s one moment when Joseph Bologna, who is Chevalier. Chevalier means, I believe it’s a soldier to the court of Marie Antoinette. His real name is Joseph Bologna, and he’s taken in this alley and there are all these people around. And first time he has seen people of color, even though he’s a person of color himself, because he’s lived in this rarefied atmosphere of upper-crust France. So he’s in this alley, which is quite wide and quite tall, and it’s a big party going on. People are cooking, playing music, so this alley has to show a transition, this alley moment, a transition that happens to him as he sits down and plays some music, so we really wanted to convey that. And there are a lot of moments where he’s going through something, where he gets drunk and gets thrown out of someplace, but as he’s walking down the hallway, we want to really have you feel what’s inside of his head and how confused. So there’s just so many moments like that. It seems like every scene almost had a moment that was key like that.

You’ve worked on many different films, including “Frozen” & “The Princess And The Frog”. How does that differ from live-action?

Well, put it this way. With live-action, there’s a lot of subtlety. You’ll see somebody walking in the distance, and we’ll hear their feet ever so slightly. A lot of nuances. And with animation, not nearly so much. So things are further forward in your face because animation’s just a little closer to you a lot of the time, even with 3D animation. And with animation, a lot of the time it’s comedic so you really have to concentrate on what can I do with sound to make this moment better, make it funnier? In Princess In the Frog, I think it’s the last scene, or I don’t want to try to sing too badly, but the song that goes is something like (singing). And it just played like that, and you see the main character getting off a street car and walking around.

And there was something missing. It kept bugging me, and I realized, oh, we need a street car bell, and it needs to be in tune with the music. So I found a good bell, pitched it in tune with the music. And so now when you see the movie, it goes (singing). So that’s just one of those little things that we’re constantly adding. In that one, there’s a scene where the song Transformation Central plays, and there’s this guy who’s this mad witch doctor, and the animators on this thing just did this amazing, crazy thing where two people turn into a whole room full of people, fireworks are going off, and just everything’s rubbery, and just things are shooting everywhere, but there’s music so the music has to be on top of everything.

But I did sound design for that, and it was a lot of fun. It took probably a couple of weeks to do, because people don’t realize how long it takes to do this, because for us, the hardest part when it comes to effects is finding the right effect. So in other words, it’s easy to edit it in once you have it, move it around and maybe change the level. But finding the right effect is the hard part. And my tendency is if there’s something that happens on screen, I try to have as few sound effects represent that sound as I can, if I can. So if somebody slams a door, we might use two door slams, a high one and a low one that’s boomy to show that they’re mad, whereas some people may cut more. They may cut six doors to really give it a lot of force. But in my mind, the more things you add, the muddier it gets, so I like to have detail.

What was one of your highlights working on “Chevalier”?

Without a doubt, the highlight was working with the director, Stephen Williams. I’ve worked with a lot of directors and a lot of good people, and he just rates up there with them. He’s a really smart guy, just fun to be around because there are just some directors who are just great storytellers. They’ll just sit there and tell stories when we’re on a break, and he’s one of them. And I find that the people who are good storytellers verbally are also visually quite good from what I’ve seen. Boy, that was the highlight. When I’m working on a good movie or a great movie, this, one of the most fun times for me is working in the mix, the final mix and hearing everything come together because it’s really a form of art. I can’t draw, can’t sculpt or anything. But when you’re molding the sound of a film, it really is like sculpting, sound sculpting.

We might say, “That footstep right there, pull that down. Where he jumps off and lands here, we want that a little bit louder. We want people to go, oh, watch the people on the left, not the right.” And we’re doing all these little intricate moves. And I just love it because, for example, a group of us, or my wife and some of the crew, went to the red carpet this weekend and heard the film in the El Capitan theater, Disney’s El Capitan Theater, which is a magnificent theater. It’s a big room, and it has a lot of reverb. Well, actually it doesn’t. For a room that big, it should have a lot of reverb but they’ve really managed the acoustics in there, so it’s got a great sound. So a lot of the scenes in Chevalier take place in concert halls, and this essentially is a concert hall where we’re playing the movie. So it was just the perfect venue for it, and it just sounded amazing.

So when we’ve had some time away from it and then get to see it again, all that mix experience and everything starts coming back and you start realizing, oh yeah, we did this, we did this, and did it. And we’re sitting there like elbowing each other. “Yeah, yeah. You remember that? Yeah, yeah.” And it’s really just a joyous time for us. We just geek out over this stuff

“Chevalier” is out now in cinemas in the US.